Longtime Educator Leaves Legacy Of Culture, Pride, Musicianship

COMMENTARY—It was my second trip to the campus of the oldest Historically Black College west of the Mississippi River, in the summer of 2000. I had been just a plus one to my best friend, Natasha Jones, while she completed her application process. I stood in the corner waiting on her, impatiently tapping my foot and rolling my eyes.

You see we were supposed to be out in the sun getting into mischief. Fresh out of high school I was ready to roam the streets of downtown Dallas with abandon. To make a long story short, I had planned to sit out a year and work, save some money.

Our family was recently rocked when my father was diagnosed with a severe case of diabetes. He was unable to work and as the oldest I came back home to work and help out. My plan was I would give him a year to get his health under control and I would resume my studies at Louisiana State University.

I was always equipped with my backpack—stocked with various sundries to survive a Texas summer day. Also, I was still carrying around my high school transcripts, test scores and the like. The then director of admissions Mr. Robinson printed me out an acceptance letter on the spot. I had no intention of attending what looked to be a ghost town of a college.

A month into the summer break, working as a cashier at Kroger had already lost its luster. And that ghost town was starting to look like an oasis. Now I just had to find a way to pay for it.

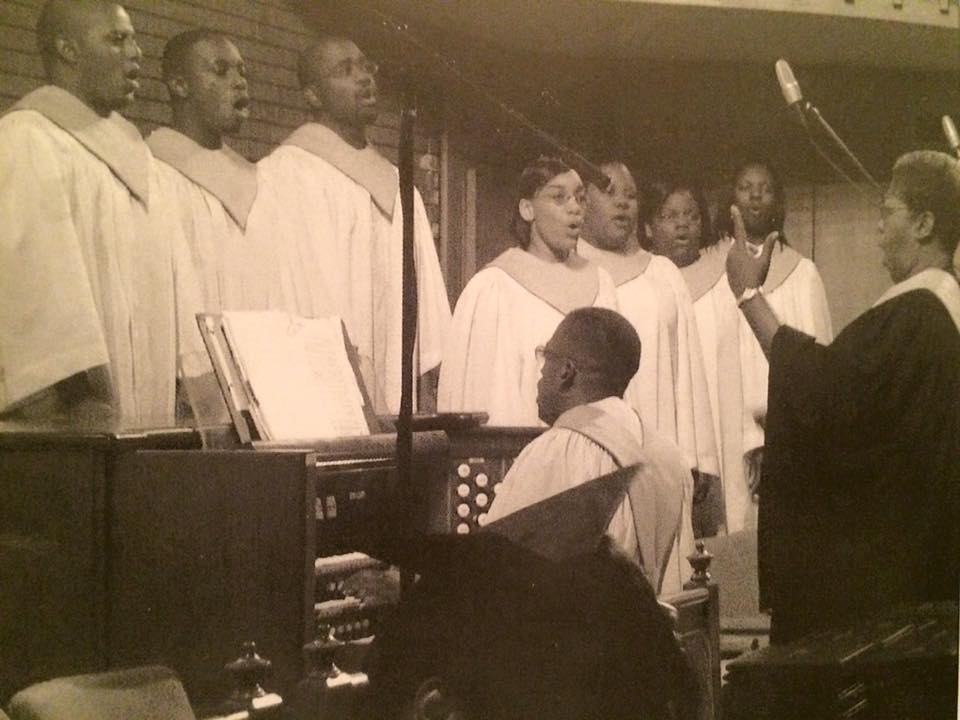

PQC Choir Days

Anyone that knew me back then, was certain that I enjoyed three things: football, music and journalism. Surprisingly, neither football or journalism fully funded my collegiate endeavors.

But then I heard that the school’s choir had institutional scholarship dollars available.

It’s funny how clear things like destiny are in hindsight. Believe me I had no idea seventeen years ago that I would come into contact with a woman that would play a part in changing my life forever. It was an alarmingly hot August day and I nervously made circles around the basement of what was then known as the Price-Branch Administration Building at Paul Quinn College.

My stomach was in knots. I had been singing in church and school choirs all my life. Blending in with others was no problem. But my voice alone was a horse of an entirely different color. The week before I called a friend from high school, Anthony Falls, I knew he would have a recommendation for me. And he did. He suggested that I sing a piece called “Vittoria, Vittoria!” by Giacomo Carissimi. We even spent hours on the phone going over the 17th century Italian aria.

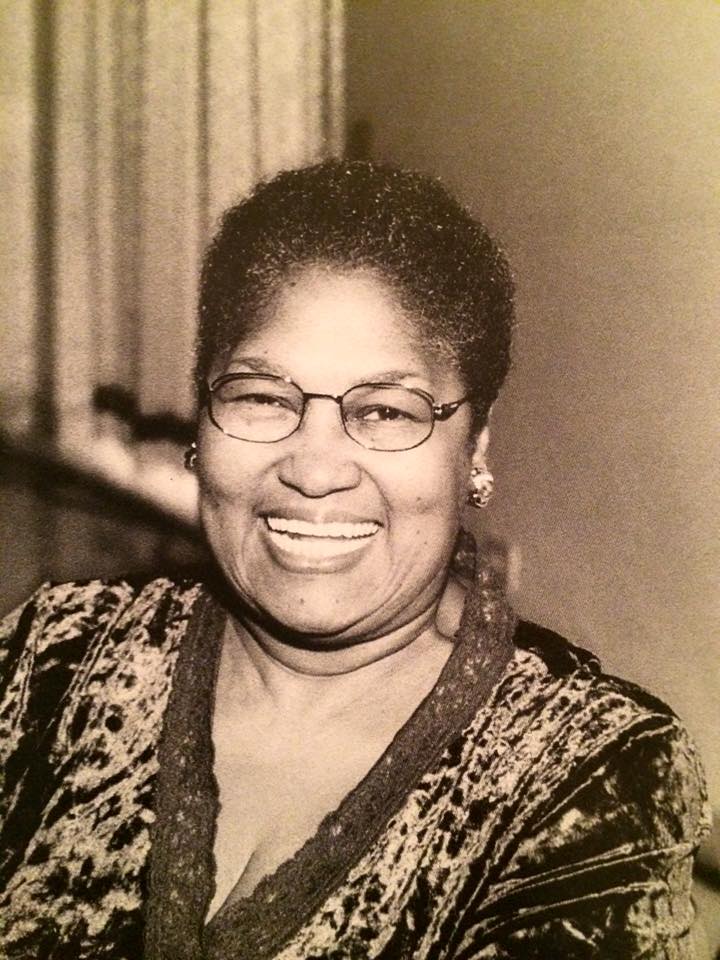

I had it down … in theory. By the time I found the choir room tucked away in the east wing of the basement I was a mess. I barely got my name and the title of my song out; much less do Carissimi’s work any justice. But Jowanda Elaine Jordan just looked at me stoically for a few seconds, that felt like a lifetime and said, “Nope that won’t do. Let’s try something else.”

After some scales and call and response, I calmed down and she was satisfied. The next four years of my education were paid for as a result of my participation in the Paul Quinn College Concert Choir.

Learning History In Music

I later realized that my fancy aria wasn’t “hittin’ on nothin” as Mrs. Jordan would say. Not because it wasn’t wonderfully composed, but because ‘Mrs. J’ was a musical preservationist. She taught me that the music of my own ancestors was as important and beautiful as anything popular culture could offer.

I grew up in church choirs singing gospel. On the rare occasion there were some difficult pieces or songs with bits of foreign language sprinkled in. But at the end of the day they were still gospel songs. In middle school I took up the piano and learned mechanics of music. In high school was a mixture of gospel, classical and show choir.

But it wasn’t until college that I learned that music could not only convey emotion, but it could house history. During my freshman year I rolled my eyes every time I heard that darn pitch pipe or got passed down some sheet music to another Moses Hogan negro spiritual.

With each tune I learned that this genre of music wasn’t just about moaning and groaning the horrors of slavery. It was a wholly independent form of communication, in a society where the ability to read and write could almost certainly result in death.

Lyrics from these songs often dealt with characters from the Old Testament of the Bible. Such as Daniel, Moses or David who had to overcome great tribulation and with whom the slaves could easily identify. Slaves many times sang about, Heaven (Freedom), the River Jordan (Ohio River) or the drinking gourd (the big dipper constellation).

Mrs. Jordan taught us that for hundreds of years history, culture and faith were innocuously passed down from generation to generation through these songs. To that end, as someone who reads and writes for a living, this takes on an entirely different meaning.

Mama J’s Legacy

Thursday of last week, I awoke to the news that the woman who made a college education a possibility, taught me about musicianship and pride in my own heritage had passed peacefully the night before.

Even though she had two biological children of her own, Crystal and Russell, ‘Mama J’ had a hand is nurturing thousands young people nationwide. She was stern and didn’t mind telling you when you weren’t up to snuff. But we all knew it came from a place of love.

At the age of 79, she had accomplished much. Jordan taught music in Dallas schools for 34 years, worked with The Black Academy of Arts and was a charter member of the Dallas branch of the National Association of Negro Musicians. She also directed choirs at Paul Quinn, Bethany Baptist Church and the South Dallas Concert Choir. Even until her time of passing she sat on the boards of several philanthropic organizations.

In 1992 she also conceived and launched the Kwei-Kwei Music Festival. Derived from a South African dialect, the phrase means “to sing a song.” Held every spring, in 2016 it was renamed the Jowanda E. Jordan Festival of Negro Spirituals.

A memorial service will be held for Jordan on Wednesday at Friendship West Baptist Church at 11 a.m. The wake will be held Tuesday night at Bethany Baptist Church starting at 7 p.m. Both services will feature musical performances from former students and choir members.