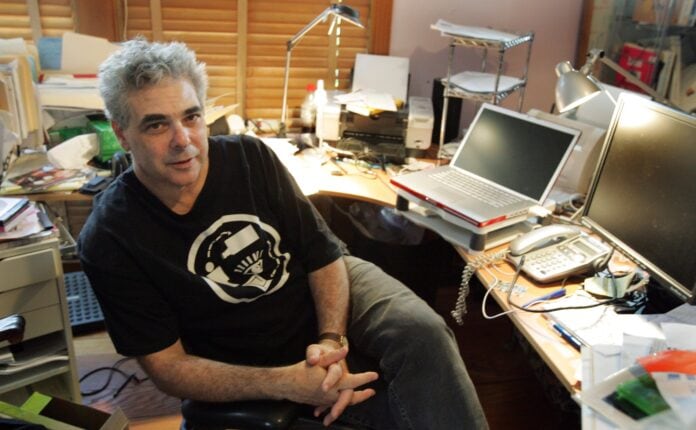

Dallas VideoFest, one of the city’s first film festivals, was started by filmmaker Bart Weiss 34 years ago at Dallas Museum of Art. Since 1987, Dallas VideoFest has given a voice to unknown filmmakers and embraced new technologies to expand the city’s film culture.

Weiss, a filmmaker and film teacher, had presented similar programs in Dallas area nightclubs before starting the four-day festival at DMA’s Horchow Auditorium. He says this fall’s DocuFest+, Sept. 30-Oct. 3 at Angelika Film Center in Dallas, will be the last VideoFest.

Artistic Director Weiss said, “Film and film festivals are about community. We look forward to being together again. In what some people think is a post-fact world, documentaries remind us that the truth matters.”

First Dallas VideoFest

At the first Dallas VideoFest, comedienne Edie Adams showcased the work of her late husband, Ernie Kovacs, from the 1950s to the early ’60s.

“Kovacs was the first artist working in television to not just stand and tell a joke but to use the camera to tell the joke,” Weiss said. “Kovacs was exploring what the art form could evolve into, which is what we’ve tried to do with Dallas VideoFest.”

The VideoFest has continued to recognize innovators with their prestigious Ernie Kovacs Award each year. VideoFest’s platform is dedicated to those filmmakers who use technologies and techniques to present their work in new and different ways. Weiss says it’s this focus that has set VideoFest apart from other film festivals.

After a full decade of screening in the DMA — a space that featured five viewing environments, including installations and a video wall — VideoFest relocated to the Dallas Theater Center. This allowed them to retain autonomy in the films screened at the festival.

“We had the whole building, and it was this incredible Frank Lloyd Wright space,” said Weiss. “We had to build everything. There was no screen, projector nor sound systems. We built a universe.”

Theater Center Years

Weiss says the VideoFest’s Theater Center years were a time when the event truly hit its stride.

“People could come hang out in the lobby and talk to each other while deciding what they wanted to see next,” he said. “We loved the community aspect of it.”

A number of local theaters have hosted VideoFest since then. Alamo Drafthouse Cinema, Studio Movie Grill, the Angelika Film Center, and a few drive-in theaters during the pandemic, have hosted the festival.

VideoFest featured a special series called “Expanded Cinema,” where the work was shown on the outside walls of the 23-story, 1001-room Omni Dallas Hotel downtown. The sound was transmitted simulcast by KXT-91.7 FM radio.

Although the available space often dictated the quantity and type of material screened, Weiss’s tastes still held sway.

“Over the years, programming for the festival has been a reflection of things I’m thinking about,” he said. “Often it was about figuring out what was best at that particular moment.”

VideoFest Fills Gap

Weiss said VideoFest sought to fill a gap for presenting work from underrepresented communities.

“It’s never been our intent to have films that would show up in the movie theater the next year,” he said. “We wanted to show things that might not be as readily accessible.”

Dallas VideoFest never became a celebrity-based festival, but focused instead on the content and aesthetic of film work. Weiss is proud of their commitment to championing interactive media — from CD-ROMs and HDTV to virtual reality — as they arrived on the scene. When VideoFest was held at the DMA, video artists had the opportunity to work with the space’s video wall, which featured stacked monitors.

In recent years, the festival has been broken down into a series of mini-festivals, the Medianale for video art, Alternative Fiction for narratives and DocuFest for documentaries.

Filmmakers Achieve Success

Many previously unknown filmmakers nurtured by Dallas VideoFest have gone on to achieve success in the film world. Dallas-based indie filmmaker David Lowery screened one of his first films at VideoFest. He went on to win a nomination for AIN’T THEM BODIES SAINTS at the 2013 Sundance Film Festival.

The festival also remains connected to the founders of former Dallas animation studio DNA Productions Inc., John A. Davis and Keith Alcorn. The festival showcased their animated films for years, including the pilot of JIMMY NEUTRON, BOY GENIUS. It continued for several seasons and became a feature film.

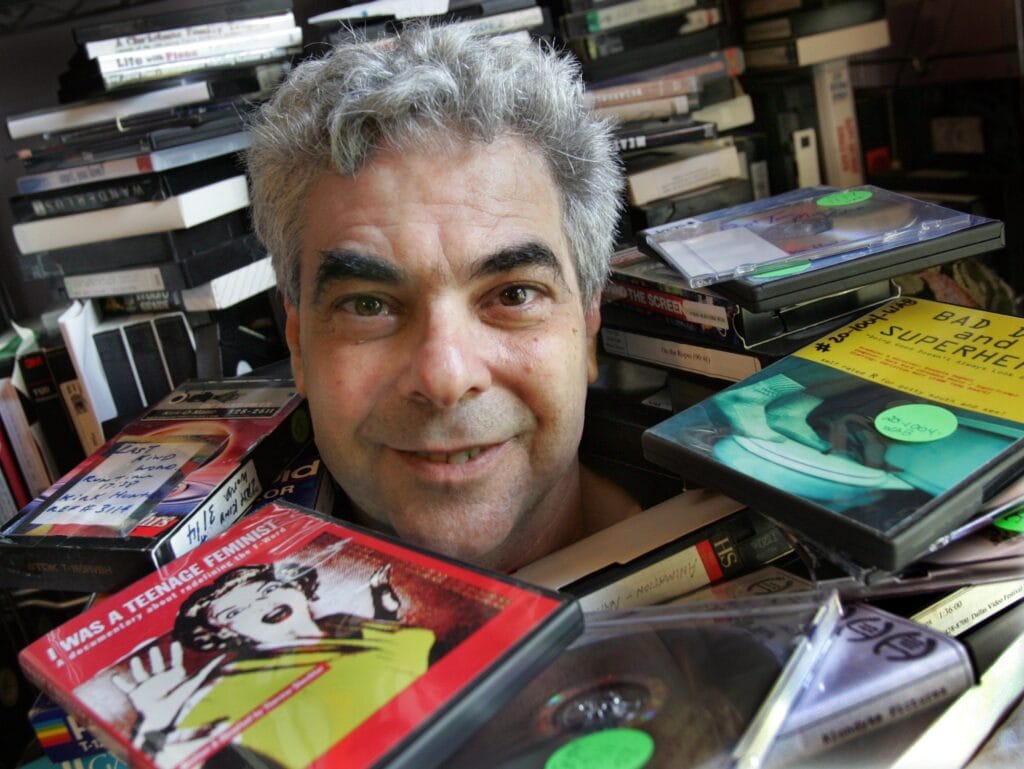

One important initiative for Weiss has been to save the work shown at VideoFest, which has been done since the second year.

“We now have tapes of what is essentially a history of this medium from 1988 to the present,” he said. “In some cases, some of the filmmakers may not have copies of the work we have.”

As Weiss reflects on the next steps, he says the end of VideoFest feels bittersweet.

“Personally, it’s sad, and in some ways, it’s somewhat of a relief,” he said. “Throughout the pandemic, I know a lot of people have gone through this questioning of ‘what is it important for me to do?’”

Video Association of Dallas

Weiss said the nonprofit Video Association of Dallas that organizes VideoFest will continue to produce his monthly show, Frame of Mind, on KERA TV public television station. They will also occasionally award the Ernie Kovacs Award, and potentially partner with other organizations to continue contributing to Dallas film culture.

As a filmmaker, Weiss looks forward to committing more time to his ongoing projects. These include a narrative series called Fire Bones, and two documentary films. The films are about Denton band Brave Combo, and noted film critics, Andrew Sarris and Molly Haskell.

During the pandemic, Weiss produced a series on “How Performing Arts Organizations Can Go Digital,” for the AT&T Performing Arts Center, and he also created a sizzle reel for Dallas Arts Month. Weiss said he hopes to reimagine what an organization could be like that does not need a large staff to produce major events, but still finds ways to influence culture.