Starting in late spring 2020, some of the patients coming into Atlanta’s Grady Memorial Hospital memory clinic began telling physician Ihab Hajjar, M.D., that

something felt different. They were having more trouble paying attention than usual, and their memories suddenly seemed much worse. It was as if their thoughts were underwater, jet-lagged, cloudy. They called it “brain fog.”

Hajjar and his colleagues also noticed something else: Many of the people reporting brain fog were African Americans. Along with neuropsychologist Felicia Goldstein, Ph.D., at Emory University, Hajjar and others began to pore through the records of about 30,000 people either diagnosed with COVID-19 or exposed to SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, to see whether they had subsequently reported issues like brain fog or memory challenges. When they compared the health records of racial groups, the researchers found that African Americans were more likely than other people to be diagnosed with memory loss or a cognitive disorder after having COVID-19.

Now a familiar term, “brain fog” is the name that patients and researchers have given to a collection of cognitive symptoms — including difficulties with attention, memory, language, processing speed, and executive function — that may follow a SARS-CoV-2 infection. These symptoms can linger for months after the virus runs its course and can range from mild to severe enough to affect a person’s day-to-day life.

“Some patients haven’t been able to go back to work,” Hajjar said. “Those who are past retirement age may have trouble keeping track of their medications, taking care of household tasks like cooking, or pursuing the activities that give their life meaning.”

These findings were what inspired Hajjar, now a professor in the neurology and internal medicine departments at the University of Texas Southwestern (UT Southwestern) in Dallas, and his colleagues to apply for a grant to look at older African Americans — one of the most vulnerable groups when it comes to COVID-19 — more closely.

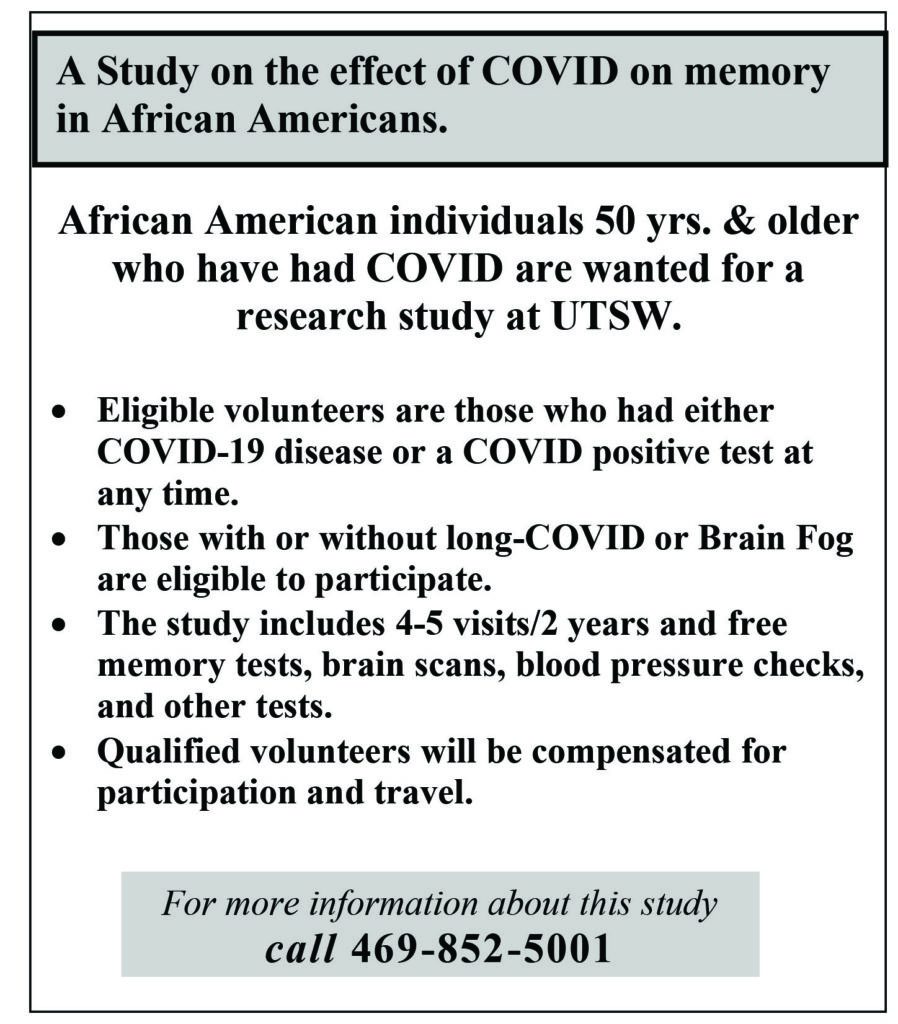

Supported by the National Institute on Aging (NIA), this project will follow more than 400 African Americans age 50 and older to learn what factors might predict cognitive challenges such as confusion and trouble concentrating after having COVID-19. Researchers also aim to understand how people are affected by these cognitive symptoms over time.

Follow the Brain Fog

At first, most people researching COVID-19 focused on the primary place the virus seemed to affect the body: the lungs. But over time, it became apparent that the virus could have lingering effects elsewhere in the body, too. “It took a while for those of us in the field to realize that this is a residual of the disease,” said Hajjar. If these or other symptoms stick around more than four weeks after an acute infection, they are considered part of the constellation of issues that make up Long COVID.

Some people with Long COVID experience cognitive symptoms; others may have fatigue, body aches, and respiratory, heart, and/or digestive challenges. Even without COVID-19, cognitive dysfunction already has a disproportionate presence in the African American community, said Hajjar, who specializes in geriatrics and Alzheimer’s disease.

Studies have found that African Americans are up to twice as likely to develop Alzheimer’s and related dementias as White people are. Hajjar is interested in narrowing in on the connection between COVID-19 and these cognitive impairments. It is possible that the viral infection itself further increases the risk of long-term cognitive impairments for older African Americans. But he also wonders whether a COVID-19 diagnosis and symptoms have landed this higher-risk population in doctors’ offices more frequently and resulted in more of them being diagnosed with cognitive impairments.

A Comprehensive Plan

To work toward answering these and other questions, Hajjar, Goldstein, and their colleagues are currently recruiting more than 400 African Americans in Texas age 50 and older who report having been infected with COVID-19. Hajjar hopes to involve enough people in the study to allow the researchers to compare the characteristics of those with and without cognitive symptoms after a COVID-19 diagnosis, then to follow people over time to determine whether these symptoms resolve or progress.

“Some patients haven’t been able to go back to work,” Hajjar said. “Those who are past retirement age may have trouble keeping track of their medications, taking care of household tasks like cooking, or pursuing the activities that give their life meaning.” These findings were what inspired Hajjar, now a professor in the neurology and internal medicine departments at the University of Texas Southwestern (UT Southwestern) in Dallas, and his colleagues to apply for a grant to look at older African Americans — one of the most vulnerable groups when it comes to COVID-19 — more closely.

Supported by the National Institute on Aging (NIA), this project will follow more than 400 African Americans age 50 and older to learn what factors might predict cognitive challenges such as confusion and trouble concentrating after having COVID-19. Researchers also aim to understand how people are affected by these cognitive symptoms over time. NIA’s COVID-19 Resources NIA shares news stories on their latest COVID-19 research.

The study aims to determine the extent of and mechanisms behind COVID-19–related cognitive symptoms in this vulnerable group. Participants will visit the UT Southwestern campus for comprehensive cognitive testing at the beginning of the study, then after 6 months, 12 months, and 24 months. These tests will look at measures including memory, executive function, language, and visual and spatial processing, as well as monitoring mood and post-traumatic stress.

The study will also examine known risk factors for dementia, measuring the participants’ blood pressure, heart rate, blood vessel function, and immune system, as well as conducting brain imaging and genetic testing. Researchers will use brain imaging and test participants’ blood and spinal fluid to look for two proteins, amyloid and tau, that are known to build up in the brains of people with Alzheimer’s disease.

Some animal studies have suggested that these proteins may contribute to cognitive problems after a COVID-19 diagnosis. Hajjar and his colleagues want to learn more about whether people without a previous history of dementia or cognitive impairments have started to have a buildup of these proteins in their brains after being diagnosed with COVID-19. The team may also study newer biomarkers linked to Alzheimer’s and dementia to learn whether they play a role in brain fog.

Between participants’ in-person appointments, the researchers will conduct phone interviews to look for other factors that might affect participants’ health, from where participants live to their access to medical care, as well as their income and their perceived stress. The researchers will also ask participants about their experiences with racial discrimination, as recent research suggests that experiencing racism is linked to memory troubles and cognitive decline.

“It’s a really very comprehensive evaluation,” said Goldstein. “We can look at how their outcomes related to cognition may relate to risk factors and predictors of good outcomes.” Related Stories Looking Ahead Hajjar, Goldstein, and their teams hope that their efforts will highlight the extent of COVID-19–related cognitive symptoms in this vulnerable group and illuminate some of the mechanisms behind these issues.

They also hope to chronicle the real impacts of post– COVID-19 cognitive symptoms on people’s lives. “I think these cognitive issues are an important problem,” Goldstein said, “and they may not come to the attention of clinicians because not all people may report that they’re experiencing these symptoms.” This research might also point to the need to incorporate a simple cognitive screening into post–COVID-19 appointments, as well as to encourage referrals for more in-depth neuropsychological evaluations. “Just asking the patient if they have brain fog may not be enough,” Goldstein said.